New York State’s Adirondack Mountains and the boggy lands surrounding them are a spare, beautiful and occasionally foreboding landscape. Today, they are a 2.5 million hectare protected forest, the largest park in the continental United States. In the mid-19th century, the region extended north from Albany to the Canadian border, more than 270 kilometers. Throughout most of history, the rough terrain has been given over almost entirely to wildlife.

But in the summer of 1869, the woods were overrun. For the first time, middle-class urbanites decided that a few weeks spent in the clutches of Nature might be survivable. In fact, they had been convinced it would be fun. For the great majority, it wasn’t. In the aftermath, they turned on the man who’d lured them there. Author, preacher and sportsman William H. H. (Adirondack) Murray never apologized. Rather, he spent the next several years justifying his pioneering call to the wildest parts of North America. Today, we call it camping.

While Murray remains obscure, the pastime he helped shape is ubiquitous. According to a recent Harris-Decima poll, nearly 12 million Canadians will camp this year. Maybe you’re one of them. Maybe you’re sitting on a soggy log right now

, absently swatting at the air, cursing the weather and wondering why the tent smells that way. If so, blame Murray.

“Before him, campers were sportsmen or Romantics,” says Massachusetts-based Murray scholar Alisa Iannucci. “They didn’t take their families. Murray advocated for camping as an activity anybody could – and should – do.”

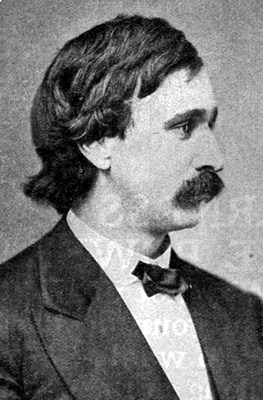

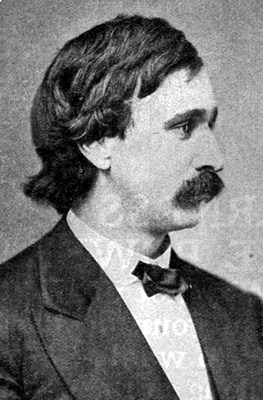

By all accounts, Murray was a strapping, Type-A personality. He was born into poverty, but his ambition drove him into the pulpit of Boston’s landmark Park Street Church. His speaking ability earned him a small fortune on the lecture circuit. This rich living allowed Murray to indulge his outdoor passions. Prime among them was the opportunity to admire God’s creatures from up-close, just before he killed them.

“Few have brought to Earth a greater variety of North American game animals, or shot them in regions more widely separated,” one contemporary biographer gushed.

Murray was also a talented writer. In 1869, at the age of 29, he completed a picturesque look at his favorite hunting ground. He called the book Adventures in the Wilderness; or, Camp Life in the Adirondacks. It combined the practical detail of a travel guide with the romantic allure of the fish-tale. More importantly, it was written by a Congregationalist minister, thus obliterating a series of moral taboos.

In the 1860s, civilized people considered any wooded area a godless wasteland drawing the unwary into sin. Hadn’t Jesus been tempted in the wilderness? Murray countered that active pursuits made a man healthy in mind, body and soul. He also swatted aside the Puritan notion that leisure was self-indulgent. Murray contended that working people couldn’t be productive without a restorative period of fruitful idleness. It is no exaggeration to say that Murray helped invent the modern notion of the vacation.

Murray was also pleasingly specific. He told people where to go, how to get there and how much it would cost. He made camping seem physically safe, morally positive and actually possible. The result was a low-level stampede. Nobody counted, but current estimates range between 2,500 and 5,000 visitors to the Adirondacks that summer, principally from Boston and New York. It doesn’t sound like much, but it was 10 times what the area could accommodate.

The first problem was the weather. The summer of 1869 bore a depressing resemblance to the summer of 2009 – cold, rainy and buggy. That was only the stage-dressing. The full tragedy wouldn’t be revealed until the cast arrived. Unaccustomed as they were to vacationing, the aspirational urbanites heeding Murray’s call made three serious mistakes. They over-packed; they overdressed; and they under-prepared.

Pouring off the trains in hoop skirts and three-piece suits, loaded down with luggage they didn’t need and couldn’t carry, most were confronted by a handful of dilapidated hotels in the town of Whitehall, on the New York-Vermont border. More importantly, they found dilapidated and completely full hotels. Most hadn’t bothered to write ahead for reservations.

At this point, the rookie campers had only reached the entry point to the promised Eden. The goal required two more legs of travel that could take another two days. First, there was carriage ride over rutted trails too primitive to call roads. Then, there were hours more in low-slung dinghies along waterways that were the only path into the mountains.

There weren’t enough carriages or boats to transport them all. The few that existed were booked. Nor could they find guides to tell them how to get to the spots Murray had recommended. Undaunted, many of the visitors hunkered down at this choke point. After a week battling black flies, most gave up. This process was repeated for months.

When they returned home, tired, poorer and none the wiser about Murray’s vision of the good life, they were upset. Many blamed the author. Some went so far as to deny there was a storybook wilderness out there at all, since they hadn’t seen it. One critic called Murray’s guide a “monstrous hoax.” It got worse.

One of Murray’s claims was that the bracing Adirondack air was not only restorative, but also curative. His book includes the tale of a consumptive relieved of illness by mountain air. That brought a flock of tuberculosis sufferers into the great unknown that summer. Several reportedly died there (though one tuberculosis victim who visited, Dr. Edward Livingstone Trudeau, would pioneer successful treatments for TB in the Adirondacks).

The fashionable amateurs who’d made the trek were lampooned as “Murray’s Fools.” Murray hit back in print and through a series of lectures. But he needn’t have bothered. The craze he had started was already spreading beyond New York and New England. It happened so quickly that, by the mid-1870s, camping was ingrained in continental consciousness.

Terence Young, a California professor, is writing a history of camping entitled Heading Out. He suggests that North Americans camp with a fervor that isn’t so much about reaching the wild as fleeing home. He also believes our emphasis on primitiveness is unique. “Most North Americans still don’t like urban life. They find it unnerving, unsettling,” says Young. “And we don’t really want to be here, not all year long at least. Camping is a way to go back, to re-enact what the pioneers did.”

Today, 1 in 5 Americans camp. The ratio is higher in Canada – more than 1 in 3.

Murray didn’t fare as well as his creation. He was eventually forced from his church, for suggesting that the patrician congregation make a greater effort at including the city’s underclass. They’d put up with his gunnery obsession. But tolerating the Irish was taking it too far. He embarked on a series of failed business ventures. In the winter of 1883-84, he ran a restaurant in Montreal called The Snowshoe. Typically, he did everything himself. Eventually, he returned to his family spread in rural Connecticut. He continued to travel widely into the wilderness. At age 64, he died in the same room in which he’d been born.

Though his name does not ring out like Emerson’s or Thoreau’s, he is rightly regarded as the father of camping. “He is the seminal figure,” says Young. “There is a before and after Murray.”

From the Toronto Star August 2, 2009.

SHARE

August 10th, 2011 | Category: Adirondacks, Nature & Outdoors